What is true of babies born to teenage mothers?

- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

Teenage pregnancy: the bear upon of maternal adolescent childbearing and older sister's teenage pregnancy on a younger sister

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth volume sixteen, Article number:120 (2016) Cite this article

Abstract

Groundwork

Hazard factors for teenage pregnancy are linked to many factors, including a family history of teenage pregnancy. This inquiry examines whether a mother's teenage childbearing or an older sister's teenage pregnancy more strongly predicts teenage pregnancy.

Methods

This report used linkable authoritative databases housed at the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy (MCHP). The original cohort consisted of 17,115 women born in Manitoba between April ane, 1979 and March 31, 1994, who stayed in the province until at least their 20th altogether, had at least one older sister, and had no missing values on key variables. Propensity score matching (i:2) was used to create balanced cohorts for ii conditional logistic regression models; one examining the impact of an older sister'due south teenage pregnancy and the other analyzing the upshot of the mother's teenage childbearing.

Results

The adjusted odds of becoming pregnant between ages 14 and xix for teens with at to the lowest degree i older sister having a teenage pregnancy were three.38 (99 % CI 2.77–4.13) times higher than for women whose older sister(s) did not have a teenage pregnancy. Teenage daughters of mothers who had their starting time child earlier age 20 had 1.57 (99 % CI 1.thirty–1.89) times higher odds of pregnancy than those whose mothers had their offset child later age xix. Educational achievement was adapted for in a sub-population examining the odds of pregnancy between ages 16 and 19. Afterwards this adjustment, the odds of teenage pregnancy for teens with at least i older sister who had a teenage pregnancy were reduced to 2.48 (99 % CI 2.01–three.06) and the odds of pregnancy for teen daughters of teenage mothers were reduced to ane.39 (99 % CI 1.15–1.68).

Decision

Although both were significant, the human relationship between an older sister's teenage pregnancy and a younger sis'due south teenage pregnancy is much stronger than that between a mother'south teenage childbearing and a younger daughter's teenage pregnancy. This study contributes to agreement of the broader topic "who is influential about what" within the family.

Background

The risks and realities associated with teenage motherhood are well documented, with consequences starting at childbirth and following both mother and child over the life span.

Teenage births result in health consequences; children are more likely to exist born pre-term, accept lower nascence weight, and higher neonatal mortality, while mothers feel greater rates of post-partum depression and are less likely to initiate breastfeeding [1, 2]. Teenage mothers are less likely to consummate high school, are more than likely to live in poverty, and have children who ofttimes experience health and developmental problems [3]. Understanding the risk factors for teenage pregnancy is a prerequisite for reducing rates of teenage motherhood. Various social and biological factors influence the odds of teenage pregnancy; these include exposure to adversity during babyhood and adolescence, a family history of teenage pregnancy, behave and attention problems, family instability, and low educational achievement [four, 5].

Mothers and older sisters are the primary sources of family influence on teenage pregnancy; this is due to both social risk and social influence. Family unit members both contribute to an private'southward attitudes and values around teenage pregnancy, and share social risks (such equally poverty, ethnicity, and lack of opportunities) that influence the likelihood of teenage pregnancy [vi, 7]. Having an older sister who was a teen mom significantly increases the risk of teenage childbearing in the younger sister and daughters of teenage mothers were significantly more than probable to get teenage mothers themselves [8, 9]. Girls having both a mother and older sister who had teenage births experienced the highest odds of teenage pregnancy, with one study reporting an odds ratio of v.1 (compared with those who had no history of family unit teenage pregnancy) [5]. Studies consistently betoken that girls with a familial history of teenage childbearing are at much college take chances of teenage pregnancy and childbearing themselves, just methodological complexities have resulted in inconsistent findings around "parent/child sexual communication and boyish pregnancy risk" [ten]. A review of family relationships and adolescent pregnancy take a chance found risk factors to include living in poor neighborhoods and families, having older siblings who were sexually active, and being a victim of sexual abuse [ten]. Research around the affect of sister's teenage pregnancy has been limited to by and large qualitative studies using small-scale samples of minority adolescents in the U.s.a. [5, 11].

To our knowledge, no previous studies have examined the impact of an older sister'south teenage pregnancy on the odds of her younger sister having a teenage pregnancy, and compared this effect with the directly effect of having a mother who diameter her first kid before age twenty. By controlling for a diverseness of social and biological factors (such every bit neighborhood socioeconomic condition, marital condition of mother, residential mobility, family structure changes, and mental health), and the utilise of a strong statistical design—propensity score matching with a large population-based dataset—this study aims to determine whether teenage pregnancy is more strongly predicted by having an older sis who had a teenage pregnancy or past having a mother who diameter her outset child before age twenty.

Methods

Setting

The setting of this study, Manitoba, is generally representative of Canada as a whole, ranking in the eye for several health and education indicators [12, 13]. At the time of the 2011 Census, approximately one.2 one thousand thousand people resided in Manitoba, with more than than half (783,247) living in the ii urban areas, Winnipeg and Brandon [fourteen]. Teenage pregnancy rates in Manitoba exceed the national; in 2010 teenage pregnancy rates in Canada were 28.2 per k, in Manitoba the charge per unit was 48.7 per 1000 [xv]. The Manitoba teen pregnancy rates in 2010 were slightly lower than rates in England and Wales (54.6 per g), and the United states of america (57.4 per 1000) [sixteen, 17].

Information

The Manitoba Population Health Enquiry Information Repository contains province-wide, routinely nerveless individual data over time (going back to 1970 in some files), beyond space (with residential location documented using six digit postal codes), for each family (with changes in family structure recorded every six months) and for each resident. Health variables are measured continuously from dr. claims and hospital abstracts (as long as an private remains in Manitoba) [eighteen].

A research registry identifies every provincial resident, with information on births, arrival and departure dates, and deaths created from the provincial health registry and coordinated with Vital Statistics files. Given approximately xvi,000 births annually, follow-up (about 74 % over 20 years) is comparable to that in the largest cohort studies based on main data [19]. Previous research using similar data shows the results are not biased past individuals leaving the province or dying. Information on information linkage, confidentiality/privacy, and validity of the datasets used have been described elsewhere [20–22]. Children are linked to mothers using infirmary birth tape information; the mother was noted in essentially all cases [23]. Sisters were divers as having the aforementioned biological mother.

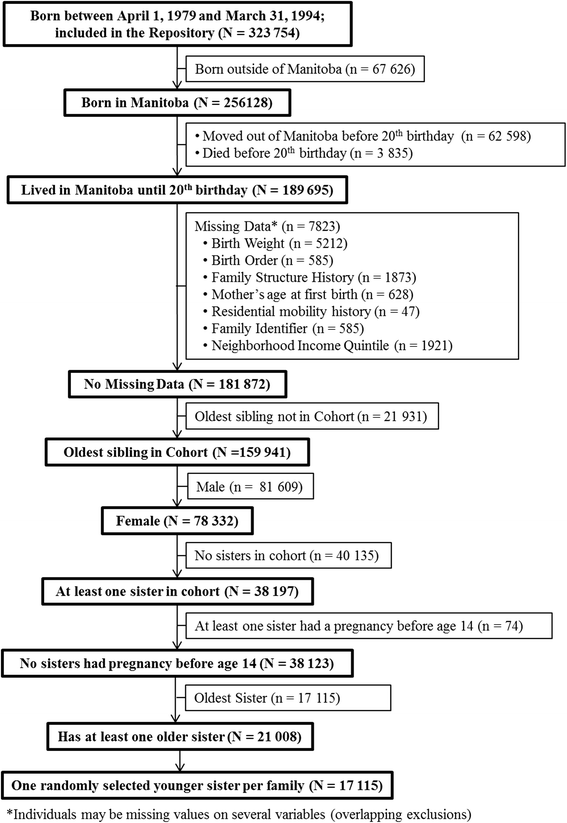

The cohort consists of women who were born in Manitoba between April i, 1979 and March 31, 1994, stayed in the province until at to the lowest degree their 20th birthday, had at least one older sister, and had no missing values on key variables. In this study, teenage pregnancies are defined as those betwixt the ages of 14 and 19; pregnancies prior to historic period 14 were excluded due to low numbers and for comparability to other studies. For this reason, families in which at least one sister had a pregnancy before age fourteen were removed (34 families). To address threats of independence, when a family had more one younger sister (more than than 2 daughters), one younger sis was randomly selected. Figure i diagrams the choice trajectory for the 17,115 individuals selected—boxes in assuming indicate the included accomplice. At historic period 14, simply over 85 % of girls in this cohort were living in the same postal lawmaking as at to the lowest degree ane older sister.

Cohort choice

Result

Teenage pregnancy was divers as having at to the lowest degree 1 pregnancy between the ages of 14 and 19 (inclusive). A pregnancy is defined as having at least i hospitalization of with a live birth, missed abortion, ectopic pregnancy, ballgame, or intrauterine decease, or at least one hospital procedure of surgical termination of pregnancy, surgical removal of ectopic pregnancy, pharmacological termination or pregnancy or intervention during labour and delivery. Pregnancy status was determined past ICD-9-CM codes (for diagnoses earlier April 1, 2004), ICD-10-CA codes (for diagnoses on or after April 1, 2004), and Canadian Classification of Health Intervention (CCI) codes in the infirmary discharge abstract database [24]. Appendix 1 presents specific codes used to determine pregnancy condition.

Independent variable

The independent variables of interest were whether an individual had an older sister with a teenage pregnancy (defined for all sisters equally described higher up) and whether an private's mother bore her first child before age 20.

Covariates

Based on an extensive literature review and availability of data in the database, several key variables describing neighborhood, maternal, and individual characteristics were included [4, 25]. Covariates mensurate characteristics in the younger sister's life before historic period fourteen. Neighborhood socioeconomic status at age 14 was measured by the Socioeconomic Gene Index (SEFI) (college SEFI score corresponds with lower socioeconomic condition), which is generated using Manitoba (Statistics Canada) dissemination areas [26]. This index combines neighborhood information on income, instruction, employment, and family structure. These neighborhoods typically include between 400 and 700 urban individuals and are somewhat larger in rural areas. Neighborhood location at age 14 was divided into urban (Winnipeg and Brandon), rural south (South Eastman, Primal, and Assiniboine Regional Health Regime), and rural mid/n (North Eastman, Interlake, Parkland, Nor-Man, Churchill, and Burntwood Regional Health Authorities). The maternal characteristic included is marital status at birth of child. An individual's number of older sisters was also accounted for.

Three time-varying covariates between birth and age 13 for the younger sister were included in the study- mental health conditions, residential mobility, and family structure change. These variables can occur at specific points in time and the timing of their occurrence tin differ across individuals. Mental health is defined using the Johns Hopkins Academy Adjusted Clinical Group (ACG) software; this software groups medical and hospital diagnoses over the course of a yr into 27 Major Expanded Diagnostic Clusters (MEDCs) [27]. If for ane year betwixt birth and age 13, the diagnoses an individual received roughshod into the 'Mental Health' MEDC, that private was categorized as having mental health conditions earlier age 13. Residential mobility was measured past at least one residential move (defined by change in six digit postal code) between birth and historic period xiii. At least one change in family unit structure (parental divorce, decease, matrimony, remarriage) between birth and age 13 was noted as 'family construction alter'.

Low educational achievement has been linked to an increased risk of teenage pregnancy [28]. The earliest measure of educational achievement available is the Grade 9 Achievement Index, which was built on a technique adult past Mosteller and Tukey using enrollment files, course grades, and the provincial population registry [29, 30]. As some of the individuals in this cohort feel their first pregnancy before completing grade ix, this covariate is but advisable for girls having their first pregnancy later their sixteenth altogether. Sensitivity testing was washed with this population to determine how strongly educational achievement affected the odds of the variables of interest.

Analytic approach

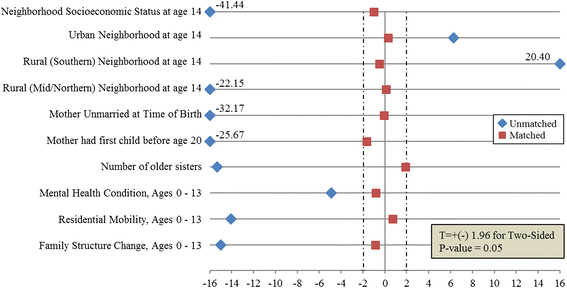

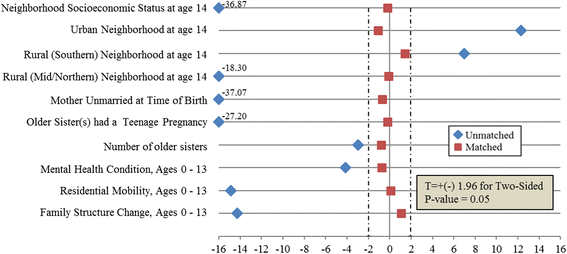

The human relationship between pregnancy during ane'southward teenage years and having an older sis who became significant during adolescence or having a mother who diameter her showtime child every bit a teenager is confounded past many measured and unmeasured characteristics. Nosotros adjusted for these misreckoning characteristics using 2:i propensity score matching [31]; two controls were matched with every instance as this "will issue in optimal estimation of treatment result [32]". Propensity score matching both enables adjustment for several confounders simultaneously and facilitates diagnostic tests to place whether the adjustment strategy created comparable exposure groups (i.e., whether women with and without an older sister who got meaning during adolescence are similar on observed characteristics) [31]. Logistic regression models were used to summate propensity scores for two responses—the predicted probability of having an older sister having a teenage pregnancy and the predicted probability of having a female parent bearing her first child earlier age twenty. For each model, we investigated the comparability of our two groups—those with and without an older sister having a teenage pregnancy, and those with and without a mother who bore her showtime child as a teenager—using two diagnostics. A kernel density plot verified that the distribution of propensity scores in our two groups overlapped [33]; each case was matched to ii controls using greedy matching [34]. Second, afterward matching, the balance of the covariates was assessed using standard differences and t-tests. Covariate residual was checked by t-statistics calculated for the standardized differences between cases and controls for each covariate before and later on matching. Any point exterior of the two vertical dotted lines signified a statistically significant divergence between the cases and controls on that covariate (at p = 0.05) (Figs. 2 and iii).

Checking covariate balance of older sis's teenage pregnancy status

Checking covariate balance of female parent' teenage mom condition

Conditional logistic regression analysis of the matched cohorts examined the impact of an older sister's teenage pregnancy and of a mother'due south teenage childbearing on teenage pregnancy. Sensitivity assay helped assess the validity of the assumption of no unobservable confounders, and assessed how strong the influence of unobserved covariates would have to be in order to nullify our findings [35, 36]. The lower limit of the 99 % confidence interval (selected to be more conservative) was used to determine the threshold unobserved covariates would accept to reach to void the observed relationship.

Results

Affect of older sister having a teenage pregnancy

Table ane displays the descriptive statistics of the covariates and outcome variables. Of the girls having an older sister with a teenage pregnancy, 40.iv % had a teenage pregnancy. This is significantly higher than the 10.three % teenage pregnancy rate amidst those non having an older sister with a teenage pregnancy.

The covariates, in general, accord with social stratification theory [37]. Teens with an older sister having a teenage pregnancy were likewise more likely to have been built-in to an unmarried mother and have a mother who herself was a teenage mother (43 % versus 14 %). At age 14, approximately 42 % of those whose older sister had a teenage pregnancy lived in Rural Mid/Northern Manitoba; only 22 % of those whose older sister did not have a teenage pregnancy lived in this region at historic period xiv. Lower teenage pregnancy was associated with residence in relatively prosperous southern Manitoba. Individuals with older sisters having teenage pregnancies were more probable to live in lower socioeconomic status neighborhood (higher SEFI scores at age 14) with higher rates of residential mobility (68 % vs 59 %), family structure change (28 % vs sixteen %), and mental health issues (19 % vs 16 %).

Later propensity score matching (on all variables in Fig. ii), the final sample consisted of 1873 cases and 3746 controls (one:2); a total of 1618 cases and 9878 controls were excluded from the analysis. T-statistics calculated for each covariate before and after matching to check for covariate balance; all covariates differed significantly in the unmatched sample and balanced in the matched sample (Fig. ii).

The concluding conditional logistic regression model indicates the odds of becoming pregnant before age 20 for those having an older sister with a teenage pregnancy to exist three.38 (99 % CI 2.77–iv.xiii) times greater than for girls whose older sis(s) did not have a teenage pregnancy (Table 3).

Impact of mother'south teenage childbearing

Table 2 displays the descriptive statistics of the covariates and issue variables. Of the girls having a teenage mother, 39.four % had a teenage pregnancy. This is significantly higher than the 13.ane % teenage pregnancy rates among those whose female parent bore her kickoff kid subsequently historic period 19.

Later on propensity score matching (on all variables in Fig. 3), the final sample consisted of 1522 cases and 3044 controls (one:2); a full of 659 cases and 11890 controls were excluded from the analysis. T-statistics calculated for each covariate showed all covariates to differ significantly in the unmatched sample and to rest in the matched sample (Fig. 3).

The concluding conditional logistic regression model indicates that the odds of becoming pregnant before age 20 for those whose mother had her get-go child before historic period 20 are 1.57 (99 % CI ane.thirty–ane.89) times greater than for girls whose mother had her first child after historic period 19 (Table 3). Thus, the bear upon of existence built-in to a mother having her first child before age xx on teenage pregnancy is much less than that of an older sisters' teenage pregnancy.

Sensitivity analysis and limitations

With the confidence interval for the first model (examining the clan between an older sister's teenage pregnancy and a younger sister's teenage pregnancy) ranging between 2.77 and 4.13, to attribute the higher rates of teenage pregnancy to unmeasured confounding rather than to an older sisters' teen pregnancy status, that covariate would need to generate more than a 2.viii-fold increase in the odds of teenage pregnancy and be a near perfect predictor of teenage pregnancy. In the second model (assessing the clan between a female parent'due south teenage childbearing and a younger sis's teenage pregnancy), the 99 % confidence interval was 1.thirty to i.89; unobserved covariates would demand to produce a much smaller increase in odds of teen pregnancy to nullify this finding.

Although linkable administrative information accept significant advantages, some of import predictors are defective. Information on involvement with Kid and Family Services (CFS) and parental use of income assistance take recently been added to the Manitoba databases, merely do not cover the cohort used here. While having a teenage mother and becoming a teenage female parent have both been linked to involvement with CFS, in 2001 less than two percent of children under historic period 18 were in intendance [38, 39]. A variable available (and applicable) for a subpopulation is educational accomplishment, which is highly correlated with both involvement with CFS and parental welfare use [40]. These two new measures would probable explicate little additional variance in teenage pregnancy. Appendix 2 describes the cohort and propensity score matching for this additional analysis, comparing these findings with the original results in Table iii. Educational attainment is measured using the Course 9 Achievement Alphabetize, a standardized measure taking into business relationship the number of courses completed in Grade 9 and the average marks of those courses. Afterward adjusting for educational achievement, the odds of teenage pregnancy for teens with at least one older sister who had a teenage pregnancy were reduced to 2.48 (99 % CI 2.01–3.06) and the corresponding odds for teen daughters of teenage mothers were lowered to 1.39 (99 % CI 1.15–i.68).

Discussion

The charge per unit differences of teenage pregnancy were similar for those whose older sister had a teenage pregnancy (twoscore.iv per 100 - 10.3 per 100 = 30.1 per 100) and for those whose mother bore her first child before age xx (39.iv per 100 - 13.i per 100 = 26.three per 100). After propensity score matching on a series of variables, the odds of becoming pregnant for a teenager were much higher if her older sister had a teenage pregnancy than if her mother had been a teenage female parent. For both older sisters' teenage pregnancy and mother'southward teenage childbearing, the odds in this study are lower than those reported elsewhere; this is likely due to the larger sample size, more than rigorous methods, and inclusion of of import predictors.

Several examinations of family histories in the literature show older sisters to have the greatest influence on a younger sis's odds of having a teenage pregnancy. Decision-making for family unit socioeconomic status, maternal parenting, and sibling relationships, teens with an older sister who had a teenage nascence were 4.8 times more probable to have a teenage birth themselves; these odds increased to five.1 if both the older sister and mother had a teenage birth [xi]. Four older studies estimated the rate of teen pregnancy to be between 2 and vi times higher for those with older sisters having a teenage pregnancy [41]. This work focused primarily on immature blackness women in the Usa and controlled for limited confounders (bated from race and age). None of the previous studies examining the impact of an older sister's teenage pregnancy controlled for mother'south teenage childbearing or time-varying factors before historic period xiv (mental health, residential mobility, family structure changes); this inquiry probably overestimated the human relationship between sisters' teenage pregnancy status.

The mechanisms driving the relationship between an older sister's teenage pregnancy and the pregnancy of a younger adolescent sister have been examined through approaches based on social learning theory, shared parenting influences, and shared societal risk [41]. Bandura's social learning theory indicates that "nearly human behavior is learned observationally through modeling: from observing others 1 forms an thought of how new behaviors are performed, and on later occasions this coded information serves as a guide for action" [7]. When sisters live in the same environment, seeing an older sis go through a teenage pregnancy and childbirth may brand this a more acceptable option for the younger sister [eleven]. Non but do both sisters take the same maternal influence that may affect their odds of teenage pregnancy, having an older sister who is a teenage mother may change the parenting way of the female parent. Mothers involved in parenting of their teenage daughters' child may have "supervised their children less, communicated with their children less about sexual practice and contraception, and perceived teenage sexual practice as more than acceptable when the older daughter's status changed from pregnant to parenting" [42]. Finally, both sisters share the same social risks, such equally poverty, ethnicity, and lack of opportunities, that increase their chances of having a teenage pregnancy [42].

Having a mother bearing her first child before age twenty was a significant predictor for teenage pregnancy. We institute daughters of teenage mothers to be 51 % more likely to have a teenage pregnancy than those whose mothers were older than 19 when they bore their first child. This is quite shut to the 66 % increment establish past Meade et al (2008), who controlled for many of the same variables except having an older sis with a teenage pregnancy, and the time-varying covariates of family unit structure change, mental health atmospheric condition, and residential mobility. Meade et al. [9] did arrange for schoolhouse functioning; in the adjusted sub-sample, the odds ratio reduced to 1.34, indicating a 34 % increment in teenage pregnancy.

Intergenerational teenage pregnancy may be influenced past such mechanisms as "biological heritability, intergenerational manual of values regarding family, the female parent'southward level of fertility, the indirect impact of socioeconomic and family environment through educational deficits or depression opportunity or aspirations, and directly through the mother'southward role modeling" [43]. Women bearing their first child in their adolescence are more probable to pass on "risky" characteristics, which could produce negative outcomes in their offspring [44]. Another machinery identified equally contributing to intergenerational teenage pregnancy is that daughters of teenage mothers have an increased internalized preference for early motherhood, have low levels of maternal monitoring, and are thus more likely to become sexually active at a young age and appoint in unprotected sex [44]. The influence of a mother's teenage pregnancy therefore works through the environment created and parenting style assumed as a outcome of a mother's teenage childbearing.

The use of administrative data to conduct wellness services research has some meaning advantages and limitations. Administrative data from a large nascence accomplice accept higher levels of accuracy is not depending on recall (such as in retrospective surveys) and is ideal for examining risk factors over fourth dimension due to the longitudinal follow-up [45]. These data—with a big N and a number of covariates—are well-suited for propensity scoring. A pregnant limitation (shared with almost all observational studies) is that certain covariates and mediating effects are unobservable due to lack of information. The data tin only capture recorded variables; for instance, only individuals seeking mental wellness treatment will receive a diagnosis, which may not be include all individuals with mental health conditions [46]. Sensitivity testing addresses this limitation, but such covariates might well have impacted study results. As mentioned to a higher place, non adjusting for involvement with child protective services (such equally CFS) is a limitation. Although the number of teenage girls involved with CFS is relatively pocket-size, they may non exist interacting with their female parent or older sister on a regular footing and thus are less probable to model themselves after their family members. The availability of an educational predictor was an identified limitation. To account for the impact of educational achievement in our total cohort, educational outcomes would need to be available for everyone for class vii at the latest (as almost all teenage pregnancies occur afterward grade 7). Since educational accomplishment by and large remains quite similar from yr to year—form ix achievement is likely to be quite like to grade 7 accomplishment [thirty]; this reduced odds ratio may ameliorate estimate the true odds. In several years, such variables tin be incorporated into models of teenage pregnancy. Additionally, we were unable to identify Ancient individuals; this is a limitation as teenage pregnancy rates are more than twice every bit loftier in the Aboriginal population than in the general population [47]. Family and peer relationships, social norms, and cultural differences volition likely never exist measured through administrative data; limiting the caste to which these confounders can be controlled for.

Conclusions

This paper contributes to understanding of the broader topic "who is influential virtually what" within the family. The teenage pregnancy risk seen in younger sisters when older sisters had a teenage pregnancy appears based on the interaction with that sister and her child; the family environment experienced by the siblings is quite similar. Much of the pregnancy chance among teenage daughters of mothers bearing a child before historic period twenty seems probable to effect from the adverse surround often associated with early childbearing. Given that an older sister's teenage pregnancy has a greater affect than a mother'south teenage childbearing, social modelling may exist a stronger risk factor for teenage pregnancy than living in an agin surroundings.

Abbreviations

- ACG:

-

Adjusted Clinical Group

- CCI:

-

Canadian Nomenclature of Health Intervention

- CFS:

-

Child and Family Services

- ICD-9-CM:

-

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

- ICD-10-CA:

-

International Nomenclature of Diseases, 10th Revision, with Canadian Enhancements

- MEDC:

-

Major Expanded Diagnostic Clusters

- MCHP:

-

Manitoba Eye for Wellness Policy

- SEFI:

-

Socioeconomic Factor Alphabetize

References

-

Chen XK, Wen SW, Fleming Due north, Demissie K, Rhoads GG, Walker M. Teenage pregnancy and adverse nativity outcomes: a large population based retrospective cohort written report. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:368–73.

-

Kingston D, Heaman Thousand, Fell D, Chalmers B. Comparison of adolescent, young developed, and adult women'due south maternity experiences and practices. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e1228–37.

-

Hoffman SD, Maynard R. Kids Having Kids: Economic Costs & Social Consequences of Teen Pregnancy. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute Press; 2008.

-

Woodward L, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Chance factors and life processes associated with teenage pregnancy: Results of a prospective study from birth to 20 years. J Matrimony Fam. 2001;63:1170–84.

-

East P, Reyes B, Horn E. Association between adolescent pregnancy and a family history of teenage births. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2007;39:108–fifteen.

-

Akella D, Jordan M. Impact of social and cultural factors on teen pregnancy. J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2011;eight:41–62.

-

Bandura A. Social learning theory. New York: General Learning Press; 1977.

-

Ferraro AA, Cardoso VC, Barbosa AP, Da Silva AAM, Faria CA, De Ribeiro VS, Bettiol H, Barbieri MA. Childbearing in boyhood: intergenerational dejà-vu? Evidence from a Brazilian nascence cohort. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;thirteen:149.

-

Meade CS, Kershaw TS, Ickovics JR. The intergenerational cycle of teenage motherhood: an ecological approach. Health Psychol. 2008;27:419–29.

-

Miller B, Benson B. Family unit relationships and adolescent pregnancy gamble: A research synthesis. Dev Rev. 2001;21:1–38.

-

East PL, Slonim A, Horn EJ, Trinh C, Reyes BT. How an adolescent'southward childbearing affects siblings' pregnancy risk: a qualitative study of Mexican American youths. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2009;41:210–7.

-

Oreopoulos P, Stabile One thousand, Walld R, Roos L. Brusk, medium, and long term consequences of poor infant wellness: An assay using siblings and twins. J Hum Resour. 2008;43:88–138.

-

Shanahan Thousand, Gousseau C. Using the POPULIS framework for interprovincial comparison of expenditures on health care. Med Care. 1999;37:JS83–JS100.

-

Statistics Canada. Focus on geography series, 2011 census. 2014.

-

McKay A. Trends in Canadian National and Provincial/Territorial teen pregnancy rates: 2001-2010. Can J Hum Sexual activity. 2012;21:161–75.

-

Office of National Statistics. Conceptions in England and Wales, 2010. Newport, CN: Function for National Statistics; 2012.

-

Kost K, Henshaw Southward. U.S. teenage pregnancies, births and abortions. 2014.

-

Nickel N, Chateau D, Martens P, Brownell M, Katz A, Burland E, Walld R, Hu Thou, Taylor C, Sarkar J, Goh C, Team TPE. Information resource profile: Pathways to health and social disinterestedness for children (PATHS Equity for Children). Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:1438–49.

-

Power C, Kuh D, Morton South. From developmental origins of adult disease to life course inquiry on adult disease and aging: Insights from birth cohort studies. Annu Rev Public Wellness. 2013;34:7–28.

-

Ladouceur M, Leslie W, Dastani Z, Goltzman D, Richards J. An efficient epitome for genetic epidemiology cohort creation. PLoS 1. 2010;5:e14045.

-

Roos L, Gupta Due south, Soodeen R, Jebamani R. Information quality in an information-rich environment: Canada every bit an case. Tin can J Aging. 2005;24:153–70.

-

Roos Fifty, Nicol J. A research registry: Uses, development, and accuracy. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:39–47.

-

Currie J, Stabile M, Manivong P, Roos L. Child wellness and young developed outcomes. J Hum Resour. 2010;45:517–48.

-

Concept: Teenage pregnancy [http://mchp-appserv.cpe.umanitoba.ca/viewConcept.php?conceptID=1248].

-

McCall SJ, Bhattacharya South, Okpo E, Macfarlane G. Evaluating the social determinants of teenage pregnancy: A temporal assay using a Britain obstretics database from 1950 to 2010. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69:49–54.

-

Chateau D, Metge C, Prior H, Soodeen R. Learning from the census: The socio-economic factor index (SEFI) and health outcomes in Manitoba. Tin can J Public Heal. 2012;103 Suppl 2:S23–7.

-

The Johns Hopkins University. The Johns Hopkins ACG instance-mix organisation (Version 6.0 Release Notes). 2003.

-

Manlove J. The influence of high school dropout and school disengagement on the risk of schoolhouse-historic period pregnancy. J Res Adolesc. 1998;8:187–220.

-

Mosteller F, Tukey J. Data analysis and regression: a second grade in statistics. Reading: Addison-Wesley; 1977.

-

Roos Fifty, Hiebert B, Manivong P, Edgerton J, Walld R, MacWilliam 50, de Rocquigny J. What is well-nigh important: Social factors, health option, and adolescent educational achievement. Soc Indic Res. 2013;110:385–414.

-

Rosenbaum P, Rubin D. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal furnishings. Biometrika. 1983;70:41–55.

-

Austin PC. Statistical criteria for selecting the optimal number of untreated subjects matched to each treated subject when using many-to-i matching on the propensity score. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172:1092–7.

-

Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the furnishings of misreckoning in observational studies. Multivar Behav Res. 2011;46:399–424.

-

Parsons LS. Reducing Bias in a Propensity Score Matched-Pair Sample Using Greedy Matching Techniques. Cary, NC: Ovation Research Group; 2001.

-

Jiang M, Foster M, Gibson-Davis C. Breastfeeding and kid cognitive outcomes: A propensity score matching arroyo. Matern Kid Health J. 2011;xv:1296–307.

-

Rosenbaum P. Observational studies. New York: Springer; 1995.

-

Singh S, Darroch JE, Frost JJ, the Report Squad. Socioeconomic disadvantage and adolescent women'south sexual and reproductive behaviour: The case of five developed countries. Fam Plann Perspect. 2001;33:251–89.

-

Jutte D, Roos Due north, Brownell M, Briggs G, MacWilliam L, Roos 50. The ripples of adolescent motherhood: Social, educational and medical outcomes for children of teen and prior teen moms. Acad Pediatr. 2010;ten:293–301.

-

Kusch L: Number of kids in care soars to all-time high. Winnipeg Costless Press. Retrieved from http://www.winnipegfreepress.com/local/number-of-kids-in-care-soars-to-all-time-high-278761011.html. 2014.

-

Brownell K, Roos NP, MacWilliam 50, Leclair L, Ekuma O, Fransoo R. Bookish and social outcomes for high-run a risk youths in Manitoba. Tin J Educ. 2010;33:804–36.

-

Due east P, Felice Thousand. Pregnancy hazard amidst the younger sisters of significant and childbearing adolescents. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1992;13:128–36.

-

East PL. The get-go teenage pregnancy in the family unit: Does it affect mothers' parenting, attitutes, or female parent-adolescent communication? J Matrimony Fa. 1999;61:306–19.

-

Kahn JR, Anderson K. Intergenerational patterns of teenage fertility. Census. 1992;29:39–57.

-

Jaffee Southward, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. Why are children born to teen mothers at run a risk for adverse outcomes in young machismo? Results from a 20-year longitudinal study. Dev Psychopathol. 2001;thirteen:377–397.

-

Jutte D, Roos L, Brownell M. Administrative tape linkage as a tool for public health research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32:91–108.

-

Bolton J, Au W, Walld R, Chateau D, Martens P, Leslie Due west, Enns M, Sareen J. Parental bereavement after the decease of an offspring in a motor vehicle standoff: A population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;179:177–85.

-

Murdoch L. Immature Aboriginal Mothers in Winnipeg. Winnipeg, MB: Prairie Women's Wellness Centre of Excellence; 2009.

Acknowledgements

The results and conclusions are those of the authors and no official endorsement by the Manitoba Eye for Health Policy, Manitoba Wellness, Active Living and Seniors, or other data providers is intended or should exist inferred. Information used in this study are from the Population Health Enquiry Data Repository housed at the Manitoba Eye for Health Policy, University of Manitoba and were derived from information provided by Manitoba Health, Active Living and Seniors and Manitoba Education under project #2013/2014-04. All data management, programming and analyses were performed using SAS® version 9.3. Aggregated Diagnosis Groups™(ADGs®) codes were created using The Johns Hopkins Adjusted Clinical Group® (ACG®) Example-Mix Arrangement" version 9.

Funding

This inquiry has been supported by the Canadian Institute for Avant-garde Research and the Western Regional Preparation Eye. The funding sources had no involvement in study blueprint, analysis and interpretation of data, in writing the article, and in the conclusion to submit for publication. None of the authors received any reimbursement for participating in the writing of this paper.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this commodity are available in the enquiry repository at the Manitoba Center for Wellness Policy. Admission to information is given upon approvals from the University of Manitoba Wellness Research Ethics Board and the Wellness Data Privacy Committee, and permission from all data providers. More than information on access to these databases can be found at http://umanitoba.ca/faculties/health_sciences/medicine/units/community_health_sciences/departmental_units/mchp/resources/access.html.

Authors' contributions

EW participated in the design of the study, carried out the assay and drafted the manuscript. LR conceived of the written report, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. NN participated in its design and interpretation of results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors' information

EW is a PhD candidate in the Department of Customs Health Sciences at the University of Manitoba. LLR is a Distinguished Professor in the Faculty of Wellness Sciences at the University of Manitoba and a founding managing director of the Manitoba Centre for Wellness Policy. NCN is a Research Scientist at the Manitoba Eye for Health Policy and an Assistant Professor in the Department of Community Health Sciences at the University of Manitoba.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Ethics approving and consent to participate

This written report involved secondary analysis of de-identified data files but, with linkages to other files where identifiers accept been removed or scrambled. Consent was not obtained from study subjects, every bit permitted under section 24(3)c of the Personal Wellness Information Human activity. Ideals approvals for this project were obtained from the University of Manitoba Health Research Ideals Board (reference number 2013-033) and the Health Information Privacy Committee (reference number 2013/2014-04).

Author information

Affiliations

Respective writer

Appendix 1

Pregnancy diagnosis codes

Teenage pregnancy is defined as females with a hospitalization with one of the following diagnoses (MCHP, 2013):

-

○ live birth: ICD-9-CM lawmaking V27, ICD-ten-CA code Z37

-

○ missed abortion: ICD-9-CM lawmaking 632, ICD-10-CA code O02.ane

-

○ ectopic pregnancy: ICD-9-CM code 633, ICD-10-CA lawmaking O00

-

○ abortion: ICD-9-CM codes 634-637 ICD-10-CA codes O03-O07; or

-

○ intrauterine expiry: ICD-9-CM lawmaking 656.four, ICD-10-CA code O36.4

Or, a hospitalization with 1 of the following procedures:

-

○ surgical termination of pregnancy: ICD-9-CM codes 69.01, 69.51, 74.91; CCI codes 5.CA.89, v.CA.90

-

○ surgical removal of extrauterine (ectopic) pregnancy: ICD-9-CM codes 66.62, 74.3; CCI lawmaking 5.CA.93

-

○ pharmacological termination of pregnancy: ICD-nine-CM code 75.0; CCI code 5.CA.88; or

-

○ interventions during labour and delivery, CCI codes v.MD.5, v.MD.60

Appendix 2

Adjustment for educational achievement

Older sister's teenage pregnancy condition

Fig. 5

Checking covariate balance of older sis'south teenage pregnancy status

Mother'south teenage childbearing status

Fig. 6

Checking covariate rest of mother' teenage mom status

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed nether the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in whatever medium, provided you give advisable credit to the original writer(southward) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Eatables license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the information made available in this commodity, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wall-Wieler, E., Roos, 50.Fifty. & Nickel, N.C. Teenage pregnancy: the bear upon of maternal boyish childbearing and older sister'due south teenage pregnancy on a younger sis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 16, 120 (2016). https://doi.org/ten.1186/s12884-016-0911-2

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-0911-2

Keywords

- Teenage pregnancy

- Familial influence

- Social modelling

- Intergenerational effects

- Linkable administrative data

Source: https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-016-0911-2

0 Response to "What is true of babies born to teenage mothers?"

Mag-post ng isang Komento